Abstract

BACKGROUND Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are widely used medications for treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and arterial thromboembolism (ATE). DOACs are favorable to the more traditional oral vitamin K antagonist (VKA)-as they do not require routine laboratory monitoring, generally have fewer drug interactions, and can be safely taken with all foods. However, DOACs can also increase the risk of bleeding events which can be severe and life-threatening. Moreover, many patients requiring DOAC therapy have chronic medical conditions, are of older age, and have history of cancers-putting them at increased risk of bleeding events. There have been multiple attempts to predict bleeding risk in patients that need DOACs, but no standard validated tool is preferred in clinical practice. Our study aims to quantify the risk of major bleeding while on DOAC therapy based upon patient characteristics. We hypothesized based upon prior evidence that a group of risk factors (Table 1) - liver disease, cerebral disease, heart disease, history of surgery, kidney disease, blood disorders, cancers, history of fall and type 2 diabetes mellitus - each increase the risk of bleeding during DOAC therapy.

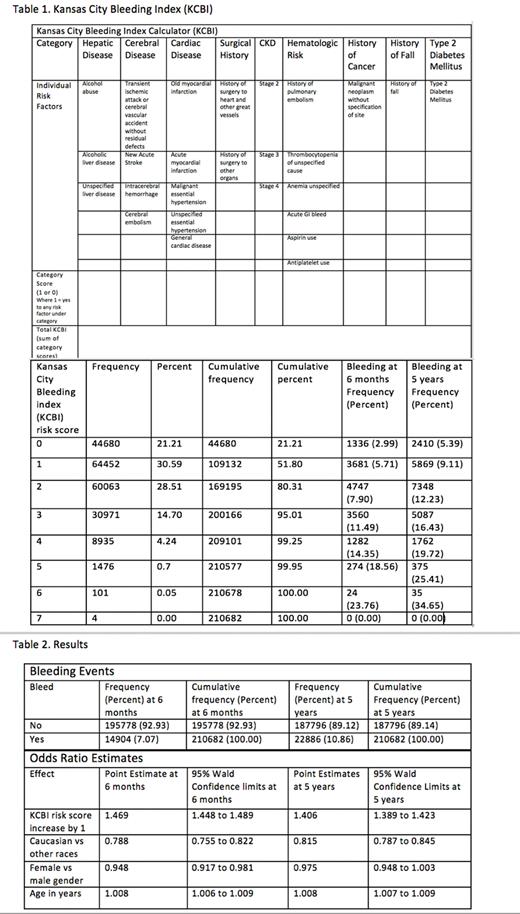

METHODS We retrospectively analyzed patient charts of 210,682 patients prescribed DOAC therapy (apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, betrixaban and dabigatran) who had a clinically significant bleeding event at 6 months and 5 years that required a hospital visit. ICD 9 and ICD 10 codes were used to search for bleeding events at different body sites and for risk factor groups based upon diagnosis. Kansas City Bleeding Index (KCBI) risk score from 0 to 9 increments was assigned depending upon the number of grouped risk factors present. Data was collected from the Health Facts database, which contains de-identified information from the electronic medical records of hospitals in which Cerner© has a data use agreement. Multivariate logistic regression modeling was used to calculate bleeding risk.

RESULTS A total of 210,682 patients were reviewed, with an average age of 68 years old (18 to 90 years). KCBI risk scores in patients ranged from 0-7 (maximum score 9); however, none of the patients had risk of 8 or 9. Majority of patients had KCBI risk scores between 1 and 2. Of the 210, 682 patients, 7.07% had bleeding events by 6 months and 10.86% had bleeding events by 5years. KCBI risk score, Caucasian race, female gender and age were all statistically significant risk factors to predict bleeding risk at 6 months (Table 2; p value <0.05). With a one-point increase in KCBI risk score, the chance of bleeding at 6 months increased by 46.9%. Caucasian race was associated with protection from bleeding with a 21.2% less likely chance to have an event at 6 months. Female gender had a 5.2% less likely chance to have a bleeding event at 6 months. With one-year increase in age, the chance of a bleeding event at 6 months increased by 0.8%. At 5 years, KCBI risk score, Caucasian race and age were significant risk factors to predict bleeding (Table 2; p value < 0.05). With a one-point increase in KCBI score, the chance of bleeding at 5 years on DOACs increased by 40.6%. Again, Caucasian race was 18.5% less likely to have a bleeding event at 5 yrs. With a one-year increase in age, the chance of bleeding at 5 years increased by 0.8%.

CONCLUSION Several risk factors exist that increase the risk of bleeding in patients on DOACs and calculating the actual risk in clinical setting is complicated. Younger age, female gender and Caucasian race were all associated with lower bleeding risk. KCBI risk score (Table 1), can be used to predict the likelihood of clinically significant bleeding requiring hospital visit based upon our study. A higher KCBI risk score correlates with a medically complex patient with higher bleeding risk requiring greater caution during anticoagulation. However, actual validation of the KBCI risk score as a bleeding predictor tool might be needed in a prospective study in an ambulatory setting. Nevertheless, it can be still used as a tool for predicting risk both at 6 months and 5 years, especially if the benefit of anticoagulation is low. Our study was limited by retrospective analysis, in-patient demographic, sicker patient condition, and clinically significant bleeding requiring hospital visit. Additionally, our patient demographic was predominantly Caucasian, limiting generalizability.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal